COLUMBIA — It’s a sad, but familiar story: an artist on the verge of greatness, cut down too soon. Such is the story of Darrel Ellis.

The exhibition “Darrel Ellis: Regeneration” at the Columbia Museum of Art resurrects the artist and gives him the recognition he never got during his lifetime.

This story is commonplace for men like Darrel Ellis, a mixed media artist who died in 1992. Like many gay men of his generation, he died young — age 33 — due to complications with AIDS. But in the short time he had, he burned bright.

He rubbed elbows with artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, and was part of Nan Goldin’s “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” exhibition. Jackie Adams, director of art and learning for the Columbia Museum of Art, said that the chaos of the time Ellis lived in made it easy for him to slip through the cracks.

“I was a coming-of-age person during the height of the AIDS epidemic in the late 80s, early 90s, and I very much remember how devastating it was to many communities,” Adams said. “When things like that happen, it can really take away so many people that should live much longer lives but aren't able to. And so their stories get lost in the tragedies and the traumas of all of those movements that happen.”

It’s only now that his work is being celebrated, in part due to this exhibition, co-organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art and The Bronx Museum of the Arts. Adams said that the Columbia Museum of Art was interested in the exhibition not just for Ellis’ story, but also for his formal experiments.

“The life of Darrel Ellis in itself is fascinating, his process and techniques are fascinating,” Adams said. “It shows a level of hands-on experimentation and physical manipulation of materials and processes that are still just very, very contemporary.”

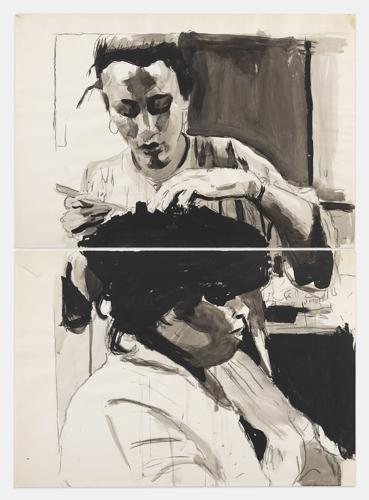

Darrel Ellis' "Laure"

Central to Ellis’ work is photography. More accurately, manipulating photography. Ellis’ father died before he was born, also at age 33. An amateur photographer, the man left behind an archive of the Ellis family and their lives in the Bronx. Ellis began playing with the photos, attempting to resurrect the feelings captured in these photos, lives that felt both familiar and estranged.

“If Darryl Ellis were with us today, I think the one thing he would want people to know about his work is that the manipulation of the materials, in itself, acts as a metaphor for family,” Adams said. “And through every different iteration, (they) become different people, different stories, different memories. ”

His manipulation takes on many forms, some more traditional, like the many sketches and paintings he made based on photographs. Others are a bit more experimental, like his swirling, distorted photographs or his mixed media collages.

Darrel Ellis' "Thomas Ellis"

Adams said that Ellis’ artwork can be read as a precursor to our Instagram age, where with the touch of a button we can mold photographs to our liking. Looking at Ellis’s work calls back to a time where the manipulation was analogue and pronounced.

“We've gotten very accustomed today to filtering our world and distorting it to the place that we project our own realities … but think about the psychological process that's happening when you're doing it,” Adams said. “What happens when you apply more of those filters? Different colors, different moods come up, different distortions, you notice something different that you didn't before. The original source photograph versus where you ended up, and all the things that go through your mind in the process, that’s essentially what Darrel Ellis was doing, but he was doing it very physically.”

Darrel Ellis' "Aunt Grandmother"

Ellis used these manipulations to create work that expressed Black beauty and community, but also the isolation he felt as a Black gay man. Adams hopes that audiences will come to the exhibition with an open mind, and allow themselves to feel the emotional aspects of Ellis’ work. As Ellis used his art to process his trauma, Adams said that audiences can process their own feelings of grief and longing, while also finding the beauty in the work.

“It's a sensitive show, it's an emotional show. And when you think about the historical context of the show, it's a really socially important exhibition as well,” Adams said. “For people who have gone through loss who have gone through grief ... who have tried to connect with relatives they've never known before, let the show be an example of ‘You're not alone, and it’s ok.’”

“Darrel Ellis: Regeneration” is at the Columbia Museum of Art until May 12. For more information, visit columbiamuseum.org.